09 Jul 2007 04:48 pm

About

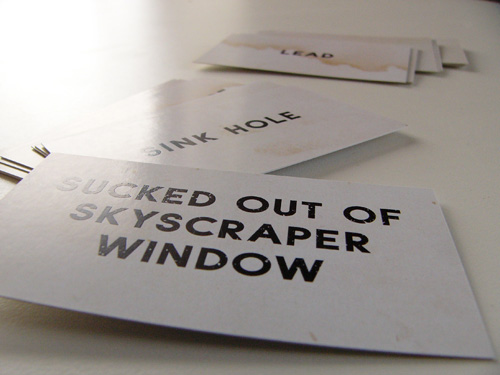

The machine had been invented a few years ago: a machine that could tell, from just a sample of your blood, how you were going to die. It didn’t give you the date and it didn’t give you specifics. It just spat out a sliver of paper upon which were printed, in careful block letters, the words DROWNED or CANCER or OLD AGE or CHOKED ON A HANDFUL OF POPCORN. It let people know how they were going to die.

The problem with the machine is that nobody really knew how it worked, which wouldn’t actually have been that much of a problem if the machine worked as well as we wished it would. But the machine was frustratingly vague in its predictions: dark, and seemingly delighting in the ambiguities of language. OLD AGE, it had already turned out, could mean either dying of natural causes, or shot by a bedridden man in a botched home invasion. The machine captured that old-world sense of irony in death — you can know how it’s going to happen, but you’ll still be surprised when it does.

The realization that we could now know how we were going to die had changed the world: people became at once less fearful and more afraid. There’s no reason not to go skydiving if you know your sliver of paper says BURIED ALIVE. The realization that these predictions seemed to revel in turnabout and surprise put a damper on things. It made the predictions more sinister –yes, if you were going to be buried alive you weren’t going to be electrocuted in the bathtub, but what if in skydiving you landed in a gravel pit? What if you were buried alive not in dirt but in something else? And would being caught in a collapsing building count as being buried alive? For every possibility the machine closed, it seemed to open several more, with varying degrees of plausibility.

By that time, of course, the machine had been reverse engineered and duplicated, its internal workings being rather simple to construct, given our example. And yes, we found out that its predictions weren’t as straightforward as they seemed upon initial discovery at about the same time as everyone else did. We tested it before announcing it to the world, but testing took time — too much, since we had to wait for people to die. After four years had gone by and three people died as the machine predicted, we shipped it out the door. There were now machines in every doctor’s office and in booths at the mall. You could pay someone or you could probably get it done for free, but the result was the same no matter what machine you went to. They were, at least, consistent.

Machine of Death is an anthology of short stories edited by Ryan North, Matthew Bennardo, and David Malki !, inspired by this episode of Ryan’s Dinosaur Comics. From January 15, 2007, through April 30, 2007, Ryan, Matt, and David invited everybody in the world to submit short stories for the book, without fee or prejudice. Hundreds of writers from five continents took them up on the offer.

Ryan, Matt and David chose their favorites from the nearly 700 submissions, and invested personal funds to pay each contributor. The manuscript was shopped for several years to agents and publishers who liked it, but were unable to sell a book full of material by largely-unknown writers.

Faced with this rejection, the editors self-published the book and, on October 20, 2010, announced that October 26 — six days later — would be MOD-Day, in which they encouraged everybody to buy the book from Amazon at once in an attempt to become, for one day at least, Amazon’s #1 best-selling book.

On October 26, exactly that happened. The book shot up the charts and hit #1 in all categories, staying there for approximately 30 hours.

On October 28, the editors got wind that Glenn Beck, on his radio program, called out MOD as being part of a “liberal culture of death” — for beating his own book (which had apparently been released the same day) to #1 on Amazon. We continue to find this hilarious.

On November 2, 2010, the manuscript was placed online, in PDF form, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–Noncommercial–Share Alike 3.0 license. That means you can (and should!) read, copy, and distribute all the stories for free.

There is also an ongoing audiobook version, which is being released as a free podcast.

Thanks to the success of the Amazon campaign, a deal was struck to distribute MOD into bookstores all across North America. The project has been the subject of many, many kind reviews and press mentions. And you can even buy the book right now:

• From TopatoCo (the editors’ own store)

• From Amazon.com

• From Amazon.ca

• From Powell’s, BN.com, or Indiebound

• From Book Depository US or UK (free worldwide shipping)

• For Kindle

• For Nook

• As an ePub for e-readers

• In Apple’s iBookstore

• As an ebook from Goodreads